The Anatomy of a Cartridge Mechanical Seal

How Design Choices Impact Performance and Maintenance

KEITH TOAL | Paradigm Seals

Cartridge mechanical seals have become the preferred standard in pumps today. When put side by side most cartridge seals look nearly identical. However, there are significant underlying differences in how each is engineered and installed. This article will detail these differences to help you understand the importance each plays in your operation and to help you choose a cartridge seal that works for you.

Designing cartridge seals to fit existing pumps is a challenge since most were originally built for packing, which requires much less space than a mechanical seal.

The first seals to replace packing were component seals, made up of separate rotary and stationary parts. Installing them required handling delicate seal faces and assembling the parts on the pump shaft before pump assembly. Once set, the seal couldn’t be moved, making impeller adjustments difficult during installation or operation.

What is a Cartridge Seal?

A cartridge seal combines all seal components into a single unit with a sleeve and collar, ensuring proper centering and spring compression without extra measurements.

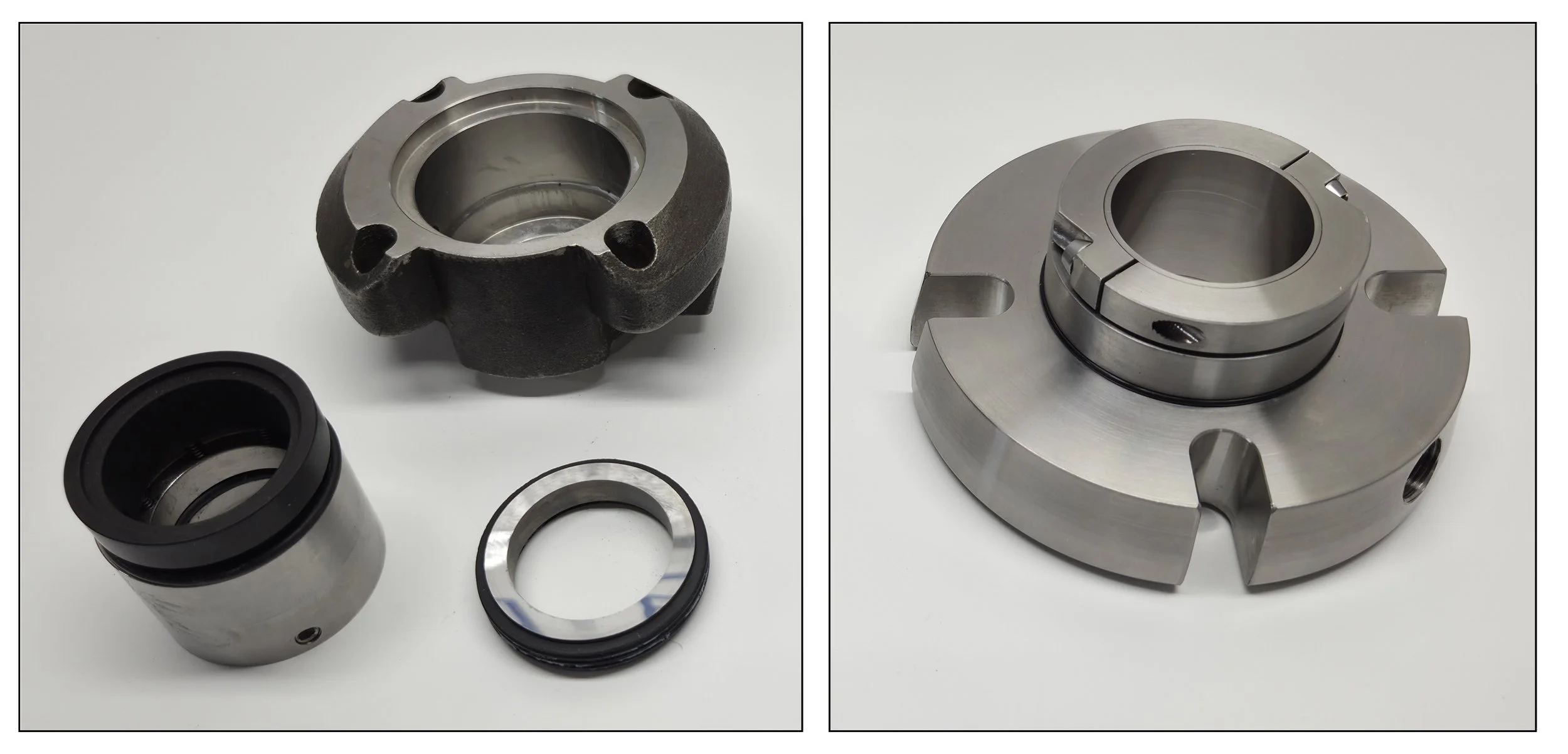

Component mechanical seal rotary, stationary and gland and a cartridge mechanical seal

Fig 1- Component and Cartridge Seals

The cartridge seal has many advantages affecting both installation and performance.

For maintenance, installation is simpler and less prone to failure. The external shaft collar can be loosened after pump assembly allowing for impeller adjustments.

Modern cartridge seals include design features that improve performance and are assembled and tested in clean conditions to protect the faces from damage and contamination.

The Key Design Features

Features can be broken down into two areas, installation and performance.

INSTALLATION FEATURES:

● Gland Gasket/Bolt holes/slots

● Centering/Setting device(s)

● Shaft Collar

PERFORMANCE FEATURES:

● Seal Faces

● Seal Face Drive

● Spring(s)

● Flush & Quench

Many factors affect cartridge seal selection, including configuration, materials, and operating conditions. Consult your seal supplier as needed for final recommendations.

Installation Features-The Gland

While some cartridge seals are made for specific pumps, most are what I term “generic.” This means the seal can fit pumps with the same shaft size but different bore and bolt dimensions. To accommodate these variations, seals use flat gaskets and slotted bolt holes. The main exception is oversized bore boxes, which require a seal designed for that bore style.

Standard bore cartridge seal Oversized/Large bore cartridge seal

Fig 2-Standard and Oversized Bore Cartridge Seals for a 1.875” Shaft

Setting/Centering Device

Since the seal is designed to fit the shaft, the gland must be centered within the cartridge to prevent contact during operation. The centering device aligns the seal as well as setting the correct spring load.

This device is typically a set of brass clips or an internal spacer. Clips must be removed after installation, while internal spacers remain in place during operation. The difference comes down to ease of installation — clips are more robust but add steps, whereas internal spacers simplify the process.

The Shaft Collar

The collar locks the seal securely to the shaft. This can be done with either a set screw or a clamp style collar.

Cartridge with set screws Cartridge with a friction drive clamp

Fig 3-Clamp and Set Screw Style Shaft Collars

Set screw collars, the most common type on cartridge seals, use multiple screws that bite into the shaft. Limited space and pump location can make tightening difficult, and the small screws can raise burrs or strip, causing removal issues or shaft damage.

A friction drive collar makes installation and removal easier while improving seal alignment, though it may slightly reduce pressure limits compared to set screws.

Performance Features-The Seal Faces

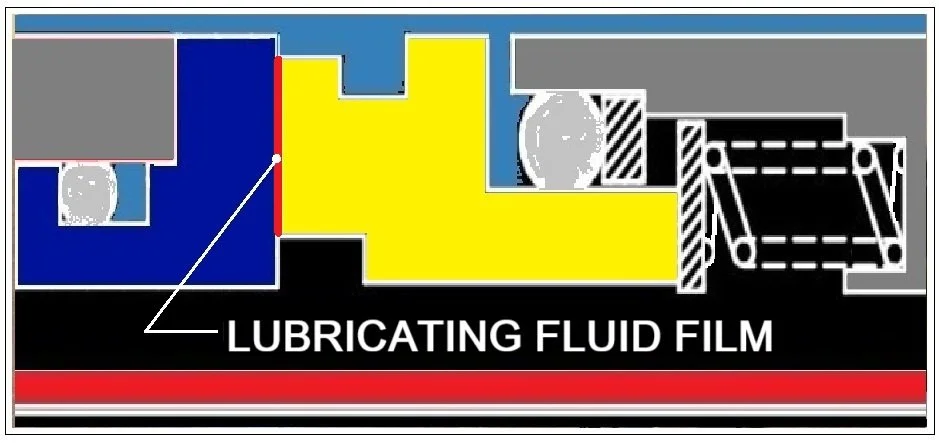

I like to call the seal faces the heart of the seal. A rotating and stationary face are held together by spring and hydraulic force. Made from carbon graphite, silicon carbide, or tungsten carbide, they’re engineered to stay flat so a thin film of fluid can lubricate and cool them — maintaining that flatness is the key to long seal life.

One face is spring-mounted to compensate for misalignment, shaft movement, vibration, and bearing play.

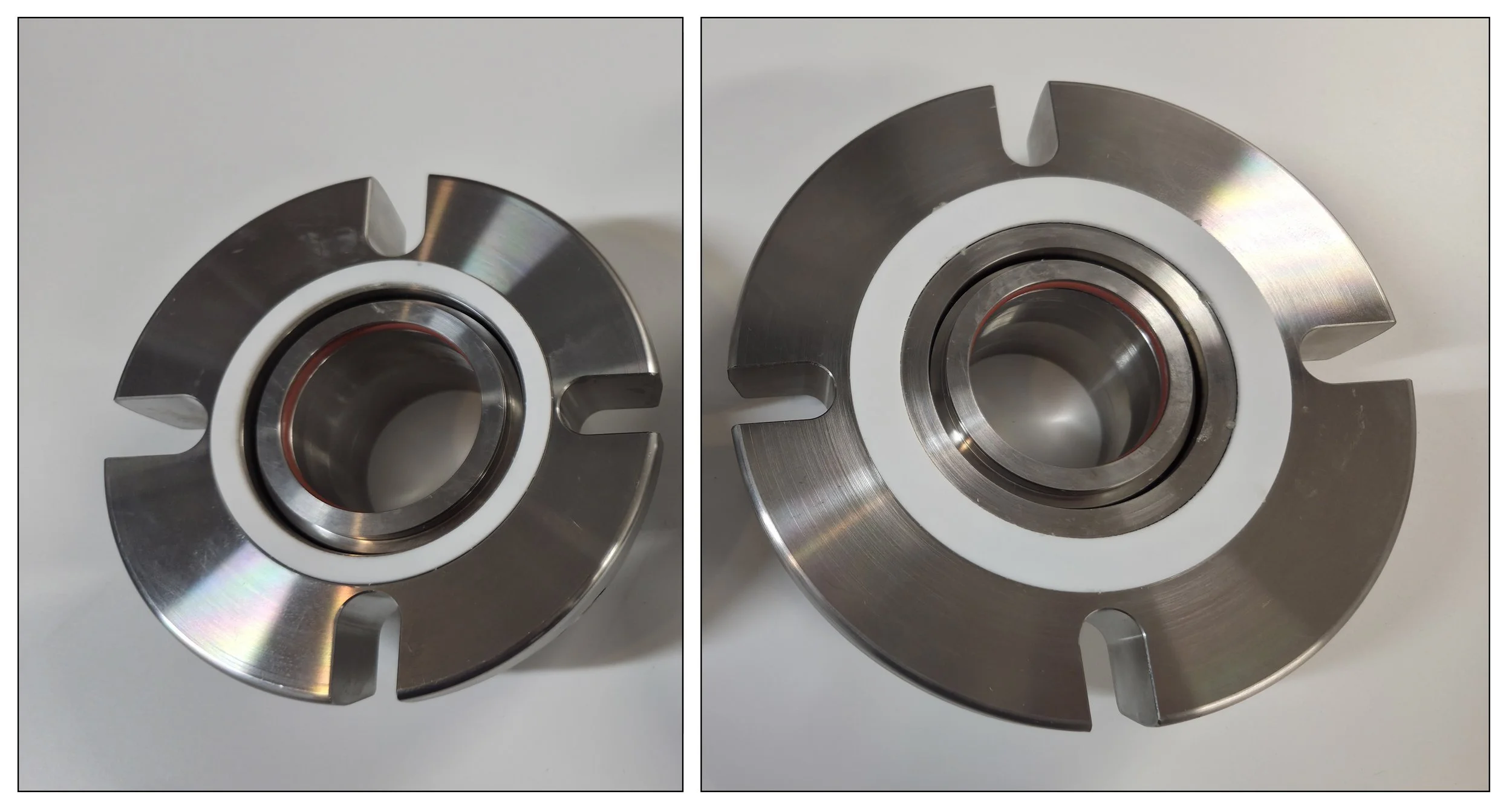

Fig 4-Cartridge Mechanical Seal Faces: Rotary (Blue), Stationary (Yellow) Lubricating Flim (Red) and springs to the far right.

Much of a mechanical seal’s technology lies in the design of its faces. With limited space, fitting the seal face into a cartridge while achieving proper hydraulic balance and maintaining flatness is a challenge. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) helps evaluate how pressure and temperature affect face distortion based on material properties, revealing clear differences between two face types — composite and monolithic — each reacting differently under the same conditions.

A composite face combines two materials — the sealing face and a metal holder.

A monolithic face, by contrast, is made entirely from a single material.

Fig 5-Composite (Shrink Fit) and Monolithic Seal Faces

The composite design uses heat to shrink-fit the face into a metal holder, saving space and reducing cost. It performs well in low-temperature, low-pressure, and low-speed applications but can lose flatness under harsher conditions, causing leakage or seal failure.

The design of monolithic faces is straightforward since they’re made from a single material. FEA confirms that they stay flatter and more stable across a wide range of operating conditions.

Seal Face Drive

Another key feature is the drive mechanism. When the pump starts, each seal face must either rotate or remain stationary as intended. This is usually achieved with small drive pins.

Contact between the face and drive pin, combined with movement or vibration, causes wear on the spring-mounted face. This wear can lead to hang-up, leakage, or seal failure. A heavier-duty drive, such as a lug drive, helps reduce wear — especially in frequent start/stop or high-vibration applications.

Fig 6-Pin Drive and Lug Drive

Springs

Spring force keeps the seal faces closed during startup and when hydraulic pressure is low. It also provides flexibility to handle misalignment and vibration.

Fig 7-Slot and Pin Wear

Seal face misalignment tends to be greater on the stationary face than on the rotary face. The rotary face mounts directly to the shaft, allowing better alignment control, while the stationary face is mounted through multiple components — the gland, gasket, stuffing box, and pump frame — increasing the chance of misalignment.

Springs can be placed behind either the rotary or stationary face. A stationary spring design minimizes shaft runout and vibration effects, improving face alignment and extending seal life. It also keeps the springs out of the process fluid, protecting them from clogging and corrosion.

Flush & Quench

The last seal feature to cover is environmental controls — or simply, the pipe taps in the gland.

A quench, with in and out ports on the atmospheric side of the seal, helps prevent leakage buildup that can cause face hang-up or allows monitoring of leakage. In my experience, quenches are rarely used in general industry but are common in crystallizing or coking applications.

The flush port is on the process side of the seal and can be used in two ways.

The first use is to circulate the process fluid around the seal — to cool or heat it for better lubrication or to reduce pressure and heat buildup. The second is to flush the seal with an external fluid, providing improved lubrication and cooling.

The flush port can be a single or multi-port (distributed) design. A distributed flush is preferred because it keeps the faces cleaner and cooler.

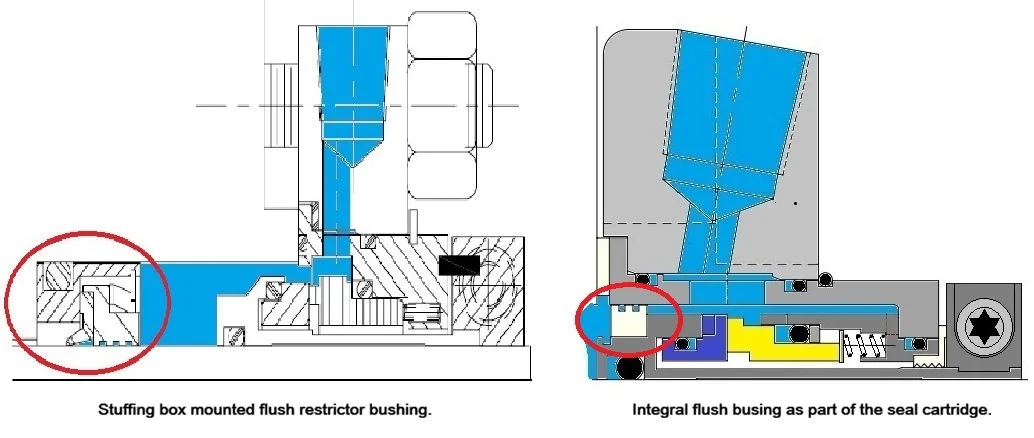

When using a flush, it’s best practice to include a throat or containment bushing to control flow. The bushing maintains close clearance to manage pressure and minimizes the use of external fluids like clean water. Your seal manufacturer can help determine the proper flow for your application.

The bushing is typically installed directly in the stuffing box, though some seals incorporate the bushing within the seal itself.

Fig 8-Flush Restrictor Bushing

Conclusion

Every business faces different challenges — from budget limits and aging equipment to less experienced crews and pumps running under off-design conditions. Understanding the design choices and how they affect performance will help you choose the seal that’s right for your application.

Keith Toal has worked in the mechanical seal industry for over 50 years working for 2 of the major seal manufacturers as well as founding 2 seal companies. He is listed as the inventor on a patent for a cartridge mechanical seal. Keith may be contacted at kt@paradigmseals.com For more information, visit paradigmseals.com.